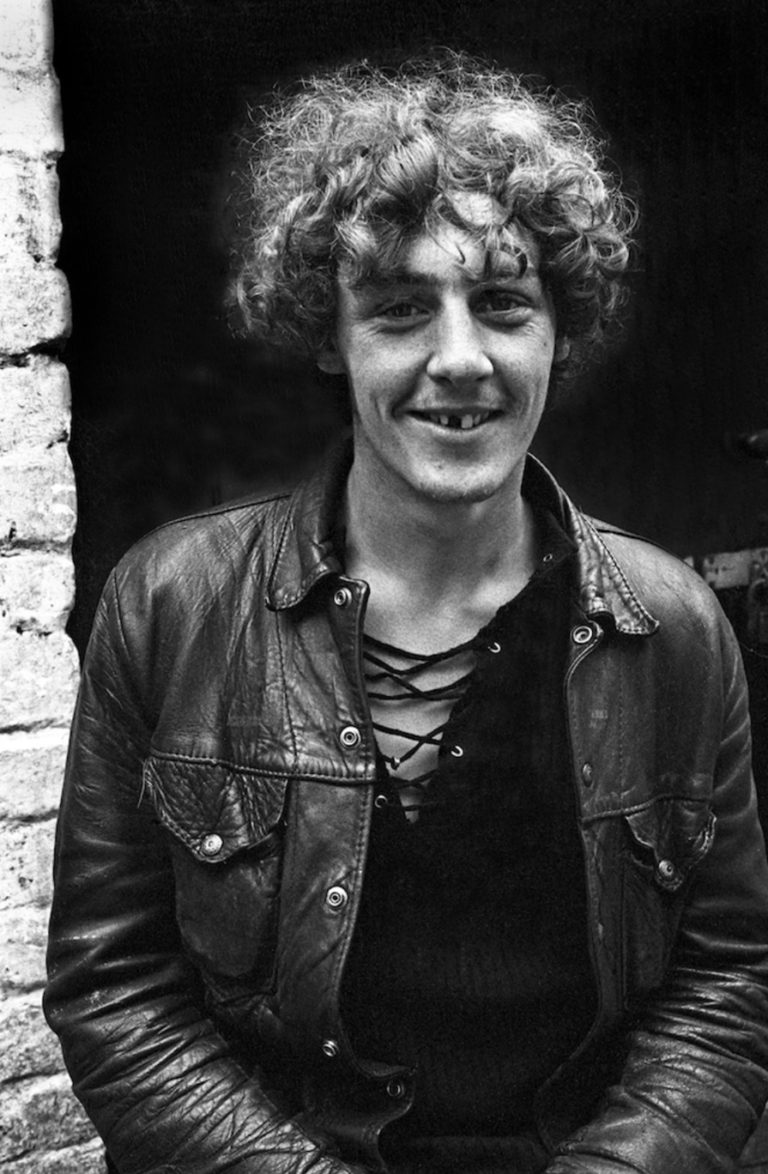

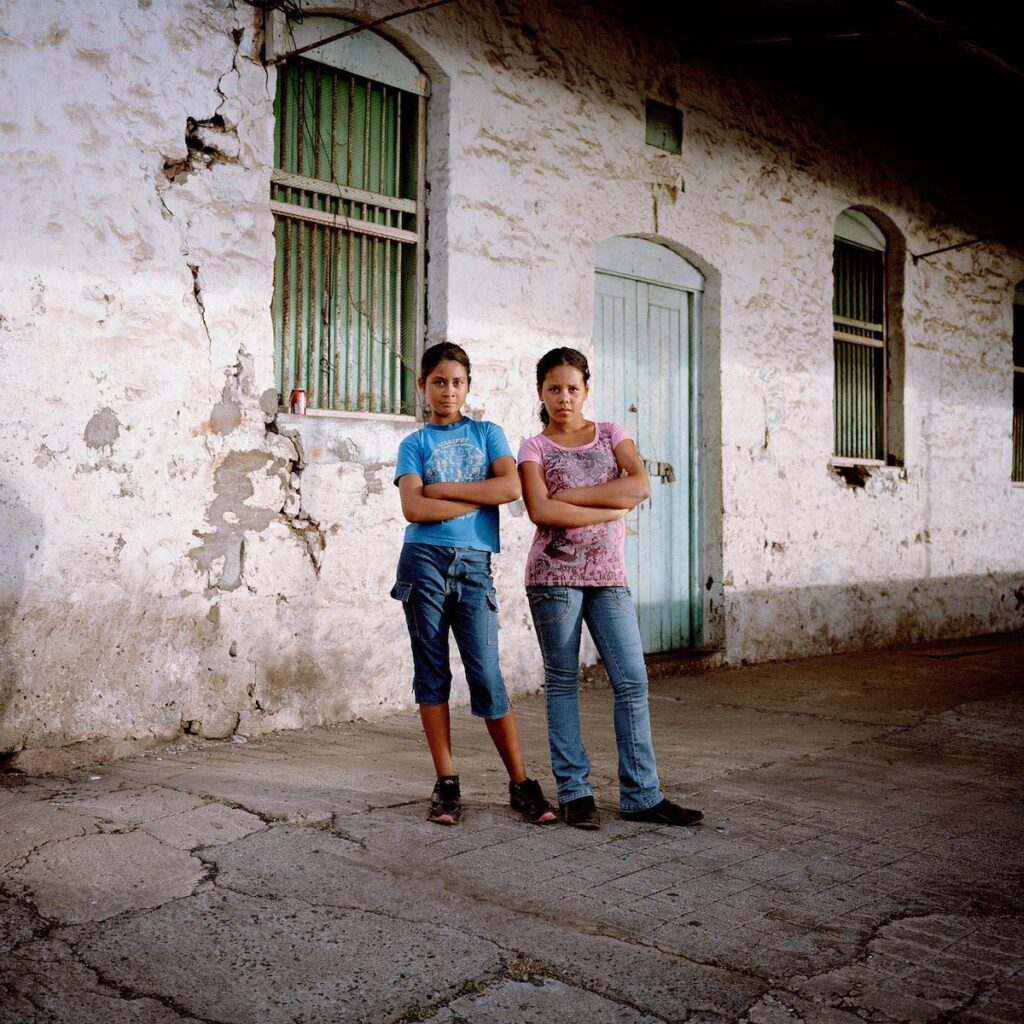

Images by Jon Tonks. Words by The Coracle.

After three days stranded in Johannesburg by swirling fog around St Helena’s beautiful peaks, the 25th flight to the island finally landed with loud clapping from all onboard.

Many passengers were locals returning home but there was a sprinkling of tourists. The long awaited 285 million pound airport has had as rocky a start as the island’s coastline due to a very blustery runway but limiting the size of the planes seems to have solved the wind if not the occasional fog problem. The inconvenience is worth it though, it’s a beautifully sunny island day.

Arrival by boat at the other end of the island, is equally distinctive. Seen from the water, Jamestown, the only town, has a stunning setting, crammed higgledy piggledy into a steep sided valley, like a jigsaw that’s still being constructed. On landing you enter a gateway through 12 foot thick walls and inside, ‘to the wonder of all who first enter this unique little ocean city, is the eighteenth century, preserved by happy accident, in every last detail’ as Simon Winchester describes it in his book Outposts. The island is famous for Napoleon but its most defining feature is its location; 1,150 miles west of Africa and 2,000 miles east of South America, 5000 people live on a rock that sits up off the continental shelf, surrounded by the raging Atlantic and with rows of jagged hills that make it look like the fortress it once was.

In the days of tall sailing ships, it was more on the map despite the lack of a harbour, after weeks at sea any land provided potential fresh water and food. From the 16th century, sailors dropped off goats and pigs to multiply and then be hunted and eaten when they returned, like a giant larder. It was also a place to take the sick, injured or dying. Dan Snow has said that ‘before aircraft or the Suez Canal it was central to the global economy. St Helena sat astride the greatest trade route in the world, the one that connected Asia with Europe, Canada and the USA.’ The great and the good stopped off here: Captain Cook obvs, Darwin, Edmund Halley, Captain Bligh, Duke of Wellington, Prince Albert, Empress Eugenie, Joshua Slocum. Think of it as the Heathrow of the great ships era.

The Portugese discovered and named it in 1502 but they passed through and after a bit of back and forth with the Dutch it was annexed by the bully boys of the East India Company in 1659, then transferred to the Crown in 1834. The island’s people are historically a mix of British settlers, soldiers, slaves, indentured Chinese workers and random sailbys that never left or were escaping their lives elsewhere. After the great fire of London in 1666, posters advertised the island’s charms and some cockneys emigrated, their accent still contributing to today’s distinctive Saint Speak (the dialect of English spoken). This melting pot has created a fascinating twist on British culture. There are the police, pubs and convoluted ceremonial occasions in uniform but the Georgian buildings are painted in Mediterranean pastel colours and the Sunday roast as often includes a curry. There’s no Costa, Pret, Fat Face or any other chain stores from the world beyond.

It’s ironic then that the place is most famous for a Frenchman: Napoleon Bonaparte. Stranding the world’s most famous general here was all about its remoteness. Defeated by the Duke of Wellington, he landed after nightfall on the 17th of October 1815, spent his first night in a bed previously slept in by his conqueror and died in 1821, bored witless and without ever seeing a Camembert again. Having escaped from a previous island prison off the Italian coast, no one wanted a repeat performance and 3000 troops were garrisoned on the island with him. The estate and house he lived at are the property of France and the morbid curious can see his death mask, he still looks less than enthused.

Napoleon isn’t the only bit of history. The writer Lawrence Green said the island ‘holds more of the strong meat of history than any other town in Britain’s colonial possessions.’ There are old forts, railways and cannons strewn around. The past here lies gently on the surface since nothing else has come along to overwrite it.

A darker history lies under the surface. Not forgotten by the islanders, but re-discovered archaeologically during construction of the airport, was a depot for people freed from slaving ships. Small boats packed with people, many children, many with injuries, they were torn from their homes in central and west Africa weeks before. From 1834, when slavery was made illegal in the empire, the Royal Navy thwarted slaving ships in the Atlantic. Until 1872 they took 437 ships and 25,000 people to St Helena, prosecuted the owners and confiscated the ships. 5,000-8000 people, tragically died in the valley camp before they could be repatriated or moved off island. In 1864, Rupert’s Valley received its last six liberated slaves from a ship so damaged that the Navy left it to sink. The refugee camp was disbanded in 1867 but some of the survivor’s descendants still live on the island today.

St Helena is now a British Overseas Territory but it was once a Crown colony and product of the empire. Cue that Star Wars music. Britain ruled the waves and needed these strategic stopping off points for refuelling, combined with the competitive land grab with which many European nations reached their tentacles across the world. At least this land didn’t belong to anyone else. In 1985 Simon Winchester said that ‘All the enginework of empire remains on St Helena’ and that is still the case today. There are expat administrators, royal portraits, a Government House and of course a real live governor general in a swan feather topped Marlborough hat. All viewed through the bougainvillea and banana fronds. Whether the UK has been good to the islanders, in return for their loyalty, has been debatable at times. Margaret Thatcher stripped them of full UK citizenship in 1981 but their full British passports were returned in 2002. The Falklands and Gibraltar uniquely kept their passports but was it a coincidence their inhabitants were white? As the tattered edges of the British empire were gradually eroded away, from Samoa to Somaliland, Guiana to Gambia, this dot in the ocean was possibly too small to make it without the mothership and despite valid complaints their people remain proudly British.

Napoleon’s fortress island is a tropical paradise when you are on it. It might have fewer Trip Advisor reviews than your local corner shop but as Stewart McPherson, who wrote the definitive guide to all the UK’s remaining outposts, describes it; ‘Jamestown struck me as an explosion of colour, history and authentic individuality unpolluted by the modern world, I feel in love with it instantly’, it’s ‘one of the few places in the world that has succeeded in preserving the best of the past whilst avoiding the worst of modernity’. With 5000 inhabitants it feels substantial, although it’s only ten x five miles, there are five or six different accents, unbelievable until you realise how hilly and distinct each area is. These hills make it beautiful and varied, there’s the lunar north, the lush tropical centre of Diana’s Peak, the mists of the Longwood uplands and the warm microclimate of Sandy Bay. Great for walkers, it’s dotted with tiny island shops to pick up a wagon wheel and beautiful mountain churches to rest in. You can swim with huge whale sharks or see the world’s largest earwig if that’s your thing. You do you. Most of all, the Saints are wonderful people, there aren’t many destinations where locals invite you into their homes for a meal. It used to be a three week sailing from Southampton but the newish airport allows you to fly via South Africa and possibly the UK in the future. Or get a ship and sail in with the wind at your back.

The wonderful photography above is courtesy of Jon Tonks who travelled 60,000 miles around the Atlantic via military outposts, low-lit airstrips and long voyages aboard cargo ships, fishing vessels and the last working Royal Mail Ship. The result was his beautiful book ‘Empire’ which you can buy here

You can also see more of his work on Instagram or buy a print from The Photographers Gallery

If you want to know more about the remaining British colonies, Stewart McPherson’s book is an epic labour of love

The best guidebook to help you actually get there is the Bradt guide