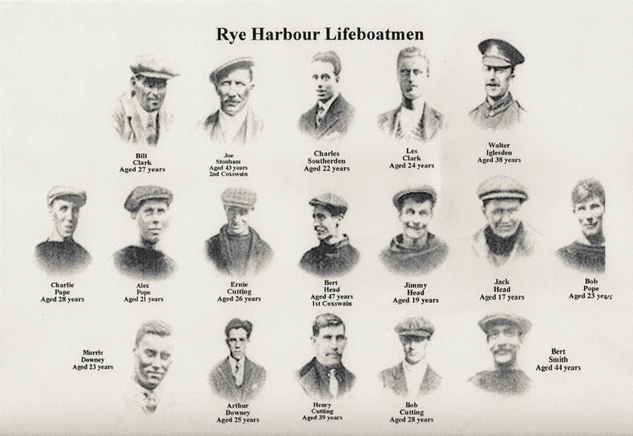

On the 15th of November 1928, 17 men rowed a small boat out into a vast storm and never returned. This was the biggest loss of life from a single lifeboat in the history of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

4.27am – The coastguard received the message; ‘Steamer. Alice of Riga. Leaking. Danger. Drifting SW to W 8 miles from Dungeness 04.30’. The Latvian steamer had collided with a larger German vessel, Smyrna, which had torn a hole in her side and ripped off the rudder. There was a south-west gale and 80mph winds in Rye Bay. The weather conditions were said to be among the worst in living memory.

5am – Maroons (warning rockets) were fired above the village to wake the lifeboat’s crew of 17 men. They left the warmth of their beds in the dead of night to attempt a rescue.

6.45am – The lifeboat station was positioned to be useable at all tides but that made it a long way from Rye Harbour village, where most of the men lived. On a sunny summer’s day it’s a 45 minute amble but in the wild conditions that night, the men were wet even before they reached the lifeboat house. After three attempts to drag the Mary Stanford across 200 yards of beach, before launching her into the rough sea, they would have been soaked to the bone.

Ryeharbour.net

6.50am – The lifeboat station received the message that the Alice’s crew had been saved by the boat they collided with. The lifeboat had no radio so Mr Mills, the signalman, launched flares to recall it. Frank Saunders ran into the sea to try and alert the crew. Both went unseen due to the poor visibility. There was so much sea spray, the salt browned the trees inland for three miles.

9.00am – The mate of the S.S. Halton saw the crew three miles W.S.W. from Dungeness, still rowing.

10.30 – Cecil Marchant, a young boy collecting driftwood saw the lifeboat capsize, as did the vicar from an upper window of the vicarage.

12.00 – The lifeboat, which wasn’t self-righting, could be seen floating upside down off the shore.

12.10 – Over the next two hours, 15 of the crew were washed up on the same beach they had left from. At least 100 men rushed to the beach and tried desperately to resuscitate the men to no avail. A Mrs Newton said ‘I shall never, as long as I live, forget the vicar kneeling on the beach and the women of the village kneeling with him, and the rain coming down like knitting needles, and they were praying’. The boat came ashore the next day at Jury’s Gap, four miles eastwards. One of the bodies was never found. Almost every family had lost a loved one. The village had lost its youth.

Original source not known

At the time this tragedy captivated the nation and was front page news in all the papers. The funeral service was held around the open grave, due to the crowds of people that wanted to show their respects and because the church was filled with over a thousand wreaths. In a BBC radio broadcast Mrs Newton recalled; ‘that was a most remarkable time – you could have heard a pin drop, there wasn’t a sound’.

There’s a road in Rye Harbour village named after the Mary Stanford, as well as a moving monument to the drowned men in the churchyard, where the dead were all buried in one grave. Even 90 years on, a memorial service is held every year. The station itself is still a long way from nowhere, sitting solemnly on its own in the middle of the bay, silent sentinel to the events of 93 years ago. It was never used again.

The Coracle

You can make a donation to the Royal National Lifeboat Institution here