CLARET I Quai Des Chartrons, Bordeaux, France

An old parcel of Britain en Francais

Only the Brits quaff claret, the rest of the world drink red Bordeaux. The only difference is the name. Why? And why is The Coracle in Bordeaux when it should be rambling around the UK?

The nation’s tipple is traditionally a pint of warm frothy beer but Britain has had a surprising impact on this part of the wine world for two reasons. There are some vineyards in the UK but according to a pre-global warming Frenchman, the wine they made could only be consumed with closed eyes and clenched teeth. As a major maritime power, in an age when sea travel was quicker than overland, Bordeaux was in the right spot for transporting and making wine, set as it is on the sunny southwest Atlantic coast. Thus the scene was set early for a flood of vino across the sea and for years that wine was largely claret. Decanter magazine has said; ‘As tea is to China, so inseparable is Britain’s affection for claret that one might be pardoned for thinking that Bordeaux was geographically part of the island’. Funnily enough, it was once just that.

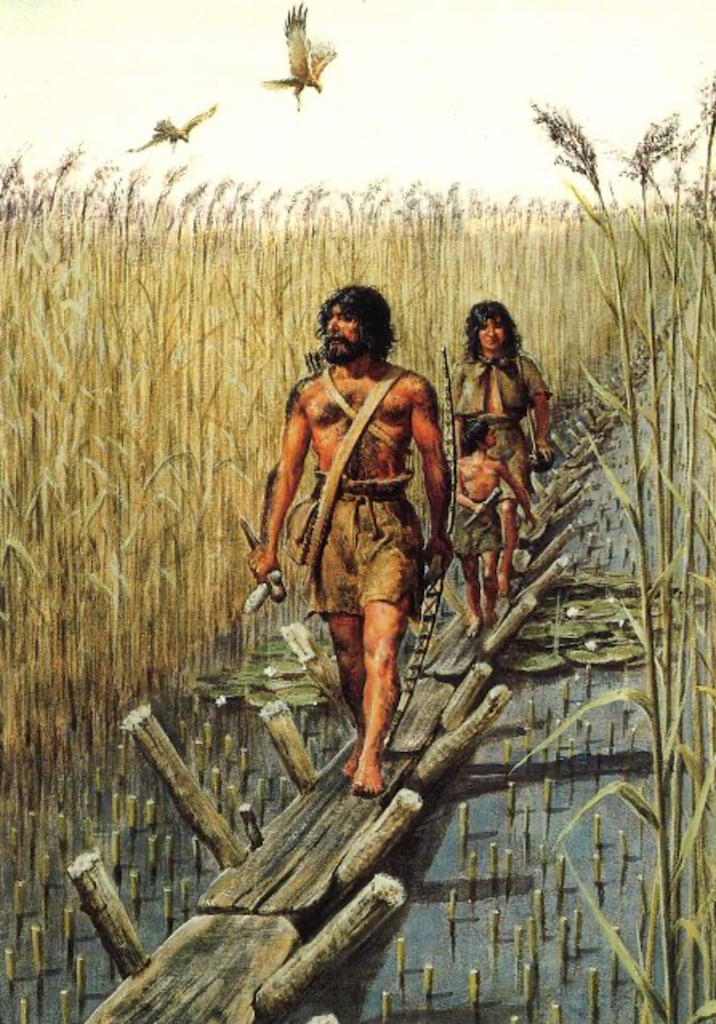

Back in 1152, King Henry II married the charismatic Eleanor of Aquitaine and Bordeaux came under English rule until 1453. It was during this time that the British first slaked their thirst for the area’s red wine. The French called it clairet and it was originally a dark rosé rather than the rich reds we associate with Bordeaux today. By 1308-1309, 102,725 tonnes of it were being shipped yearly to Scottish and English shores. English kings and dukes frequently reinforced the privileges of the wine producing districts that they ruled, as well as downing the stuff themselves, 1,152,000 bottles crossed the channel for the wedding of Edward II. Yes 1,152,000 bottles. In return, foodstuffs like grain loaded the empty ships back to Bordeaux. At the time this was the busiest shipping route in the world. The wine suited the English and Scottish palate and it was only later that the French took an interest. How Gauling.

The slight problem for all concerned was that clairet needed drinking within a year, before it turned as sour as a British wine. Around the second half of the 17th century, it underwent a transformation. English and Scottish traders helped invent stronger and darker bottles and the corks to seal them. Before this it was sold in giant barrels called hogsheads and you trusted your local merchant not to mix it with Ribena. Wine became separated into old and new styles, linked to specific chateau rather than broad unpredictable areas. Gradually the quality improved and it became a richer and darker drink. Many expats lived in Bordeaux to service this growing trade. They built their houses on the banks of the Garonne river on the Quai des Chartrons, with elegant drawing rooms and huge cellars stretching 1000 feet under the road. Family clans of English and Scots maintained their position for centuries and went on to own wine chateaux themselves. Sold in the coffee shops of London and Edinburgh, by the beginning of the 18th century, et voila, clairet became claret!

Whilst claret has a tradition going back centuries, the British have always had a penchant for ageing their favourite tipple. The improving effect of time was partly discovered by barrels of wine that had been on the hot and salty journey to India and back. It possibly also helped that this was the drink of choice for the aristocracy, with their grand piles and ancient cellars, the wine could rest undisturbed for decades. Michael Broadbent, the famous Christies wine auctioneer, described claret as the ‘Staple drink of the English upper classes’ and it still has a whiff of the tweedy shooting party about it. This was a world of gentleman’s clubs and sporting analogies, often mocked by the tabloids when long lost bottles popped up for sale at outrageous prices.

In the 1870s and 1880s, a pesky little bug called phylloxera turned claret buying into a bit of a gamble and people moved on to port and other wines. But personal connections with Bordeaux were strong enough for it to survive. Nowadays the city’s old merchant houses are more likely to be boutiques with clothes elegant as the wine. Global warming is having the biggest modern day impact on claret, with hotter summers and more extreme weather events. Ironically those same weather shifts are enabling the British to make their own less teeth chattering wine but claret is still in our blood.

Gordons wine bar in London is a fine place to quaff some claret if your membership of Brooks has run out.

Traditionalists should buy a case or two at Berry Brothers or Averys of Bristol.

Billionaires Vinegar by Benjamin Wallace is a true life detective story about some very old claret.

The original clairet wine is still available in some places, it’s a fresh and fruity little number that might fade over the final third.