There aren’t many jobs about which someone would say; ‘everything is good about it, I’ve been very lucky’. Steve Shelley’s family have been thatchers for six generations, over the last 200 years. That’s a lot of thatching action. It seems like it might be a tough job, out in the elements 40 feet up on a steeply sloping roof but Steve cited the independence, the freedom and the views! He also emphasised the need to be a free spirit and to work with the weather and understand its ways. A northerly wind brings cold weather, a south-westerly indicates milder weather is coming. They don’t teach you this shit at school but maybe they should. They also don’t teach you about the old country trade that is thatching but it’s a growing business once more.

There’s a solidity and depth to a thatched roof that goes back through the ages. Steve says that there’s been thatch on buildings since man walked the earth although you could equally say that it’s been used since man stopped nomadically walking the earth and started to build more permanent dwellings. Thatching reflects the universality of man and despite different patterns, techniques and raw materials, it’s seen everywhere from palm topped South Seas island Fales to Ethiopian Tukuls to Danish Kirker. In the UK, it was practically the only material until the use of slate tiles increased from the 1800s. It’s often now a sign of fashionable rusticity rather than rural depression. Either way, it’s historically been very local, the designs reflecting their immediate area and the materials that were nearest to hand.

Steve used to grow his own thatch for 40 years but it’s gradually become a more specialised and legislated process. It takes 4-5 acres for an average sized house, that’s an average sized house, not an average sized Fale ;). The thatch in the house here is long straw from Wiltshire but the spars that hold it in place are from Poland. Thatched houses in Essex, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire feature long wheat straw, water reed or combed wheat reed so Steve works with all of these. Heritage varieties of wheat are the best for thatching which reinforces the interconnectedness of the process with the old land; in parts of Scotland people used to put their old peat-smoked thatch on their garden to enrich the soil, thereby completing the circle of life. One of the best things about thatched roofs are the insulating properties. The semi-hollow reeds trap hot air in them but reflect the heat in Summer. Cool.

It hasn’t always been a bed of roses though. There were dark days for thatchers as men left the land to work in towns and cities. This broke the natural cycle of generations but having persevered Steve is now booked a year in advance. Many thatched buildings are listed so you have to replace like with like but there is a good collaboration between the listed building authorities and many thatchers. This house was last thatched, by Steve of course, 30 years ago but you can ‘spar coat’ by overlaying a new thatch onto old, some roofs that use this process are now over 500 years old. Maybe Steve’s great-great granddaughter is already booked in for that job.

If you need some thatching, get in touch with Steve via his son Dan here

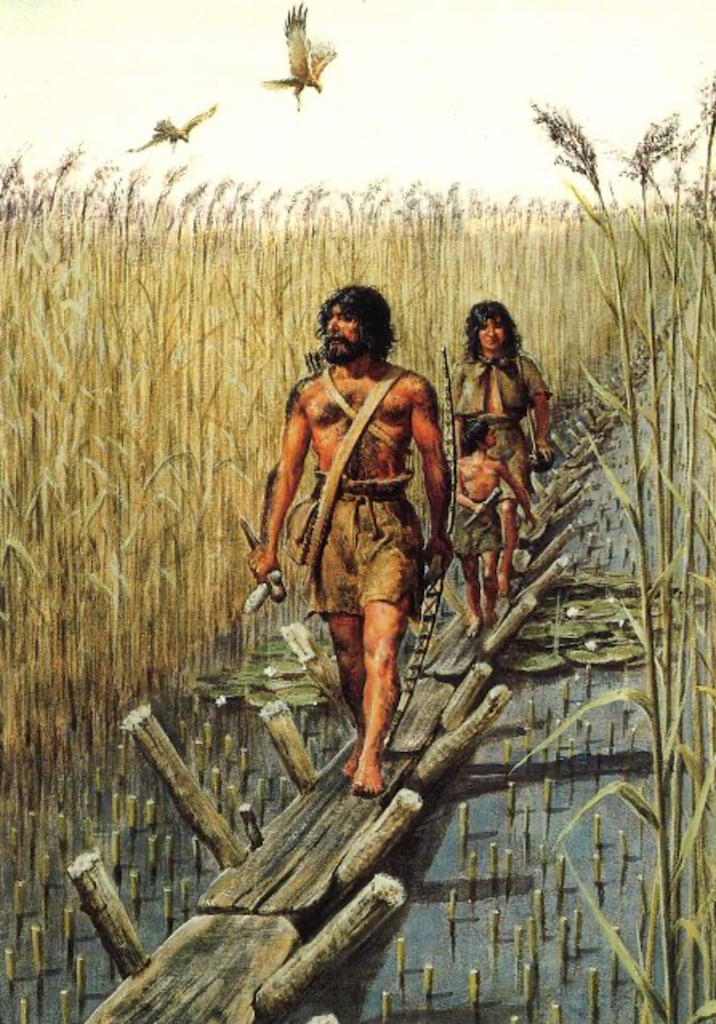

Left to right – George Shelley (grandfather), Stan Shelley (father), Steve Shelley.

Image from Shelley family archives